Behind the autism spectrum Understand article

Research into the genetics of the autism spectrum is increasing our understanding of these conditions, and may lead to better ways to diagnose and manage them.

Desmond; image source: Flickr

The first time I encountered autism was in the summer of 2004 while working as a children’s camp counsellor. That year, one boy stood out. His name was Peter, but everyone called him ‘the professor’. Peter knew a great deal and read a lot; to the others he seemed to be a genius. However, he didn’t make friends easily and mainly played alone.

Staff became concerned when they realised that Peter didn’t laugh at jokes, avoided eye contact and grew angry if he couldn’t sit in the same seat. The camp manager thought Peter might have autism. His parents then admitted that Peter had been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome but that they hadn’t mentioned it because Peter was so keen to attend the camp. ‘The professor’ was able to stay until the end of the camp and we all learned a lot from him.

Asperger’s syndrome is one of a group of similar disorders

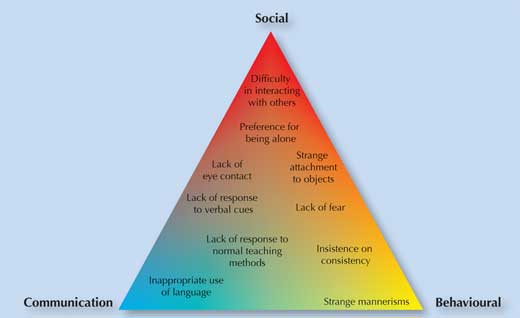

My experiences with Peter made me want to understand and research the biological basis of Asperger’s syndrome. This is one of three disorders with similar, but distinct, symptoms (see box on autism spectrum disorders), which are classified as autism spectrum disorders (ASD). ASD starts in early childhood and continues throughout adulthood. Sometimes people are not aware that they have it. Common symptoms include lack of eye contact and difficulties maintaining relationships, often combined with learning difficulties (figure 1). It can be hard for sufferers to integrate into society or to live independently.

Image courtesy of Andreas Chiocchetti

The autism spectrum disorders

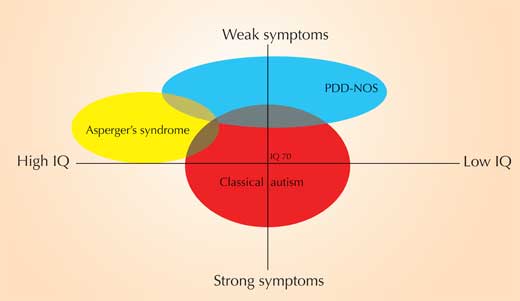

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are defined by certain communication, social and behavioural difficulties (figure 1). ASD is a ‘spectrum’ because different people experience the symptoms differently, and with varying degrees of severity. There are three sub-types – Asperger’s syndrome, early childhood (or classical) autism and pervasive developmental disorders not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) – with varying symptoms and severity (figure 2 and table 1).

Image courtesy of Andreas Chiocchetti

| Early childhood (or classical) autism | Asperger’s syndrome | PDD-NOS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Early childhood | Usually later onset | Not specified |

| Social level | Impaired | Impaired | At least two of these three are affected |

| Language level | Impaired | Not impaired | |

| Behavioural level | Impaired | Impaired | |

| IQ | High functioning: IQ > 70; low functioning: IQ < 70 | IQ > 70 | IQ > 35 |

ribbon. The jigsaw puzzle

pattern symbolises the

complexity of the autism

spectrum

Image courtesy of Melesse;

image source: Wikimedia

Commons

ASD has both genetic and environmental causes

ASD prevalence in the general population is estimated at about 1 % and rising, mainly due to increased awareness and a broader diagnosis. It is estimated that up to 80 % of ASD has a genetic basis (see box on ASD heritability). Geneticists believe that ASD is caused by a combination of different variations in several genes, rather than one single mutation or gene variant.

If 80 % of ASD is genetic, the other 20% must be explained by environmental factors. Only a few environmental factors have been proven to increase the risk of ASD, including parental age and rubella infection during pregnancy. Despite the widely publicised scare in the UK, however, there is no evidence to suggest that vaccines increase the risk of developing ASDw1, w2.

Another risk factor for ASD is gender: boys are four times more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than girls. Perhaps some risk factors are carried on the X chromosome (of which males only have one copy, meaning they have no second, healthy, chromosome to compensate) or in genes that are activated during male development.

Some other disorders, such as fragile X syndrome, show similar symptoms to ASD: around 50 % of people with fragile X have autism-like symptoms. Fragile X patients have a known mutation in the FMR1 gene, which alters a protein essential for normal brain function.

ASD heritability

Twin studies have shown that the cause of ASD is largely genetic (up to 80 %). These studies analyse twins who have grown up together where at least one child has ASD. Monozygotic (identical) twins have the same genetic information, whereas dizygotic (non-identical) twins are more like normal siblings: they share around half of their genetic information but have experienced many of the same environmental factors (e.g. parents and home care).

If a disorder has a purely genetic basis, it will always affect both monozygotic twins. In dizygotic twins, if one has a genetic disorder there is a 50 % chance that the other twin will have it too. Studies have shown that if one twin has ASD, the chance of the other twin being affected is around 80 % for identical twins, and about 30 % for non-identical twins; these figures include both the genetic contribution and the effect of the environment that was shared by the twins. From these data, the average genetic contribution to ASD has been estimated to be 50-80 %. The remaining contribution is environmental, so to develop ASD, a person would usually need both a genetic predisposition and an environmental trigger.

plasticity, which is crucial for

learning, memory, emotional

recognition and use of

language

Image courtesy of illuminaut;

image source: Flickr

ASD is linked to synaptic plasticity

Genetic research on ASD focuses on identifying variations linked to ASD. Researchers are genotyping ASD sufferers and their parents to identify the inheritance patterns of particular high-risk alleles. My collaborators and I are also comparing the DNA of healthy people with the DNA of people diagnosed with ASD.

Studies have identified several rare mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, which are more common; see box) linked to ASD. Geneticists have also discovered that, in ASD sufferers, copy number variations (CNVs; see box on genetic variation) affect coding regions of DNA more often than in the general population.

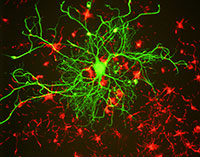

By analysing the proteins that these genes encode, we have shown that they are important for energy metabolism, protein synthesis and signalling in neurons. It seems that these variations affect the ability of brain cells to make and maintain connections. This process, called synaptic plasticity, is crucial for learning, memory, emotional recognition and the use of language.

Genetic variation

Each of us carries many genetic variations. These variations include single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and copy number variations (CNVs), as well as rare mutations that are limited to patients with ASD. Mutations are alterations in the genetic code, including deletions and insertions or nucleotide replacements. SNPs occur when one single DNA nucleotide is different, e.g. at a particular place in the genome, one person might have an adenine (A), whereas another person might have a guanine (G) nucleotide.

Most people have two copies of each gene, one from each parent. However, some people have CNVs: these people might have more than or fewer than two copies of a gene, or might even be missing a sequence entirely.

SNPs and CNVs are normal, fairly common (particularly in non-coding DNA) and do not usually cause problems. However, some variations, if they are found in or near an important gene, can cause illness. Certain damaging SNPs, CNVs and rare mutations are associated with ASD (figure 3).

Image courtesy of Andreas Chiocchetti

in tissue culture. Mutations

linked to ASD appear to affect

the brain’s ability to make and

maintain connections

Image courtesy of GerryShaw;

image source: Wikimedia

Commons

Genetic diagnosis provides hope for better treatment

Currently ASD is diagnosed by interviewing the parents and observing the ASD sufferer. The diagnosis can be influenced by the parents or the psychiatrist’s personal bias. It is also a very time-consuming process. Therefore, a fast, objective and reliable diagnostic tool is needed.

Knowing which genes or genetic variations are responsible for ASD makes it possible to design new diagnostic tools. Understanding the molecular mechanisms involved might also enable new medications or treatments to be developed.

Personally, my main reason for doing this research is to explain the biological basis of ASD to both ASD sufferers and the general public to help reduce the stigma associated with the condition.

Web References

- w1 – Wikipedia offers a good overview of the controversy surrounding the combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

- w2 – The British medical community also responded to the MMR scare.

Resources

- This novel is told from the point of view of a boy with Asperger’s syndrome:

- Hadden M (2004) The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. London, UK: Random House. ISBN: 9781400032716

- Fans of Jane Austen’s novels will find this a fascinating and enlightening study:

- Ferguson Bottomer P (2007) So Odd a Mixture: Along the Autistic Spectrum in ‘Pride and Prejudice’. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley. ISBN: 9781843104995

- ASD from the perspective of a special education teacher:

- Rich L (2005) Casey’s Wall: A Novel. Bloomington, IN, USA: iUniverse, Inc. ISBN: 9780595378579

- Chapter 16 of Bad Science covers the MMR scare in the UK:

- Goldacre B (2008) Bad Science. London, UK: Harper Collins. ISBN: 9780007240197

- The animated film Mary and Max (2009; Director: Adam Elliot; Australia) tells the curious and touching story of two unlikely pen pals, Mary and the autistic Max.

- The character of Raymond, the autistic central figure in the 1988 film Rain Man is based on a real person.

- If you have concerns about a pupil, family member or friend, it is advisable to speak to a doctor or psychiatrist. You should not rely on self-diagnosis or web-based diagnostic tools, as there is a lot of misleading information on the Internet.

- The following websites, however, may be helpful:

- Readers who are interested in consulting the primary literature may find the following articles useful:

- Chiocchetti A et al. (2011) Mutation and expression analyses of the ribosomal protein gene RPL10 in an extended German sample of patients with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 155(6): 1472-1475. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33977

- Freitag CM et al. (2010) Genetics of autistic disorders: review and clinical implications. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 19(3): 169-178. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0076-x

- Hallmayer J et al. (2011) Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Archives of General Psychiatry 68(11): 1095-1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76

- Holt R et al. (2010) Linkage and candidate gene studies of autism spectrum disorders in European populations. European Journal of Human Genetics 18(9): 1013-1019. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.69

- Leblond CS et al. (2012) Genetic and functional analyses of SHANK2 mutations suggest a multiple hit model of autism spectrum disorders. PLoS Genetics 8(2): e1002521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002521

- PLoS Genetics is an open-access journal, so this article is freely available.

- Lichtenstein P et al. (2010) The genetics of autism spectrum disorders and related neuropsychiatric disorders in childhood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 167(11): 1357-1363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10020223

- Liu XQ et al. (2008) Genome-wide linkage analyses of quantitative and categorical autism subphenotypes. Biological Psychiatry 64(7): 561-570. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.023

- Pagnamenta AT et al. (2010) Characterization of a family with rare deletions in CNTNAP5 and DOCK4 suggests novel risk loci for autism and dyslexia. Biological Psychiatry 68(4): 320-328. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.002

- Pinto D et al. (2010) Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature 466(7304): 368-372. doi: 10.1038/nature09146

- Download the article free of charge from the Science in School website or subscribe to Nature today.

- Weiss LA et al. (2009) A genome-wide linkage and association scan reveals novel loci for autism. Nature 461(7265): 802-808. doi: 10.1038/nature08490

- Download the article free of charge from the Science in School website or subscribe to Nature today.

Review

This informative article gives an insight into the autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and their distinguishing features. It is helpful as a source of information for any teachers who have students with ASD, for understanding the genetic mutations associated with ASD, and as an example of how genetics and environment can affect phenotype.

The article could be used in biology lessons about the brain or behaviour, or in discussions of synaptic plasticity. Suitable comprehension questions include:

- How do studies show that autism is largely inherited?

- What are the risk factors for autism?

- What kind of genetic variations are linked to autism?

Shaista Shirazi, UK