Van Gogh’s darkening legacy Understand article

The brilliant yellows of van Gogh’s paintings are turning a nasty brown. Andrew Brown reveals how sophisticated X-ray techniques courtesy of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France, can explain why.

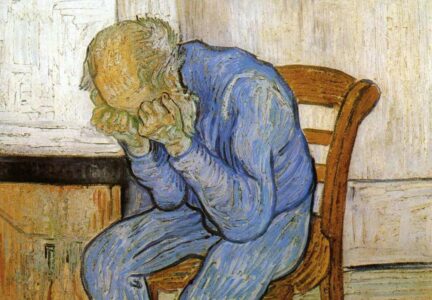

Along with his expansive brush strokes, Vincent van Gogh’s (1853-1890) choice of vibrant and often unrealistic colours to convey mood and emotion were central to his unique style, one which had a powerful influence on the development of modern painting. The new-generation pigments of the 19th century made it possible for van Gogh to create, for example, the rich yellows used in his celebrated Sunflowers. These striking shades, used in many of his works, contained one of these new pigments, called chrome yellow. Unfortunately, more than 100 years after it left van Gogh’s brush, chrome yellow has in some cases darkened visibly to a less than striking brown, a phenomenon that recently caught the interest of a group of scientists.

Image courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Image courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Image courtesy of Acacia217; image source: Wikimedia Commons

Image courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

An international team led by Koen Janssens of the University of Antwerp, Belgium, believes that chemical changes to chrome yellow (PbCrO4 · xPbO), brought about by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, are responsible for its colour transformation (Monico et al., 2011). The darkening of the pigment in sunlight has been known since its invention. Studies in the 1950s demonstrated that it is caused by the reduction of chromium from Cr(VI) to Cr(III) (see Figure 1, below). Until now, however, the precise mechanism was unknown, and the degradation products were uncharacterised.

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

Historic paint tubes

To address these unknowns, Janssens’s team began by collecting samples from paint tubes belonging to van Gogh’s contemporary, Flemish painter Rik Wouters (1882-1913). Some tubes contained unmixed chrome yellow paint, whereas others contained paint of a lighter shade of yellow, formed by mixing chrome yellow with a white substance. The researchers artificially aged the samples under UV light, expecting to observe a colour change after several months. To their surprise, in only three weeks, a thin surface layer of the lighter yellow paint had darkened significantly to a chocolate brown. The unmixed samples changed either comparatively little or not at all. “We were amazed,” says Janssens.

Having identified the sample most likely to be undergoing the fatal chemical reaction, the team subjected it to sophisticated analyses based on X-rays. Much of the work was carried out at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF)w1 in Grenoble, France, where two techniques, XRF and XANES, were used to detect, with extreme sensitivity, the spatial distribution and oxidation state of selected elements in the paint samples (see box).

Analyses revealed that the darkening of the thin surface layer of pigment was linked to a reduction of the chromium in chrome yellow from Cr(VI) to Cr(III); this fits with what has been observed for industrial paints based on lead chromate. In addition, the Cr(III)-containing degradation product was identified for the first time as Cr2O3 · 2H2O, better known as the pigment viridian green. But how can a green pigment’s presence explain the brown colouration observed in the researcher’s experiments? The scientists suspect that the reduced chromium in viridian green is formed during the oxidation of the oil component of the paint. It is this oxidised form of the oil, together with the mixture of green and any remaining yellow pigment, that may be the root of the brown colouration.

Using the X-ray techniques, the researchers were also able to show that the mixed, lighter-coloured paint contained sulphur compounds. They concluded that these compounds were somehow involved in the reduction of chromium, explaining why there was comparatively little darkening in the unmixed paint samples.

Shining the X-ray beam on van Gogh

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of the Van

Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Having uncovered the chemistry of the reaction in isolated paint samples, the scientists sought to ask whether the darkening of the surface layer of yellow paint in samples taken from two of van Gogh’s paintings, View of Arles with Irises (1888) and Bank of the Seine (1887), could be attributed to the same phenomenon.

XRF spectroscopy was used to map the chemistry of the region encompassing the interface between the dark surface layer and the underlying unaltered yellow layer of paint. XANES spectra were collected at specific points within these regions. The findings mirrored those of the previous experiment: the reduced form of chromium, Cr(III), was found in the darker surface layer, suggesting that its presence here was responsible for the brown colouration. Furthermore, Cr(III) was not distributed uniformly, but occurred in loci that also featured sulphate- and barium-containing compounds.

Chemically, these regions resembled the lighter yellow paint samples from the previous experiment, further supporting the researchers’ conclusion that sulphur compounds were involved in reducing chromium (see equation below). Because of their white colour, van Gogh blended powders containing such compounds with chrome yellow to create the lighter shades that were vital in creating the brightly lit scenes characteristic of a certain period of his life.

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

One important question remained: how does the supposed trigger for the reaction, UV light, actually work? Quite simply, it supplies the reactants with the energy needed to overcome the activation energy barrier, allowing the reaction to proceed (see Figure 6, below).

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

What can be done?

Janssens’s team has exposed the chemistry that underlies the darkening of van Gogh’s paintings. But can we use this knowledge to rescue the artist’s work? Ella Hendriks of the Van Gogh Museumw3 in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, has her doubts: “Ultraviolet light…is already filtered out in modern museums. We display the paintings in a controlled environment to maintain them in the best possible condition.” Part of what constitutes a controlled environment is the maintenance of a low temperature in the museum. As a general rule, an increase of 10 ºC increases the rate of a reaction by a factor of 2-4, and reduction of chromium is no exception to this.

So if both UV levels and temperature are already controlled, what more can be done for van Gogh’s paintings? There is a more radical alternative: rather than slow the degradation process, attempt to reverse it altogether. “Our next experiments are already in the pipeline,” says Janssens. “Obviously, we want to understand which conditions favour the reduction of chromium, and whether there is any hope of reverting pigments to their original state in paintings.”w4

Although turning back the hands of time in this way would be the supreme solution, Janssens admits that the prospect of reverting the altered pigment to its original colour is at present rather unlikely. Nevertheless, the scientists’ work offers us reassurance that we are doing everything we can to preserve van Gogh’s paintings, and hope that future generations can appreciate what this great artist achieved.

Studying art with a synchrotron

The chemical characterisation of precious works of art can be problematic. It is only possible to take a few very small samples for analysis, and these often consist of a diverse mixture of complex compounds in heterogeneous states of matter. To overcome these challenges, scientists use techniques based on X-rays. The more powerful and precise the X-rays are, the better the quality of the analysis. The most potent X-rays available are produced by a synchrotron sourcew2 (see Figure 2, below). In this study, two spectroscopic techniques at ESRF were used on the paint samples: XRF and XANES.

Image courtesy of EPSIM 3D / JF Santarelli, Synchrotron Soleil; image source: Wikimedia Commons

XANES

XANES spectroscopy relies on the physics of X-ray absorption. Atoms of a particular element absorb X-rays in a characteristic way. By looking at the X-ray absorption spectrum, which is the pattern of X-ray absorptions of a particular sample (Y axis) against the energy range of the X-rays (X axis), it is therefore possible to identify the sample’s constituent elements. High-resolution X-ray absorption spectra are usually collected in particular energy regions (called XANES) that are close to an absorption edge of an element of interest (see Figures 3, below, and 4). Such detailed spectra can show what oxidation state the element of interest is in. This information was of great interest to the researchers.

Image courtesy of Atenderhold; image source: Wikimedia Commons

(B) An absorption edge in detail. When we zoom in on a seemingly smooth absorption edge, we find that it is decorated with a number of smaller impressions relating to correspondingly smaller absorptions. The region at the leading edge (shaded in blue) of the absorption edge is referred to as an X-ray Absorption Near-Edge Structure (XANES, the blue box) and it corresponds to electrons making transitions to unoccupied energy levels close to those that they left. The XANES region was used by the scientists analysing the van Gogh paintings, because it can provide information on the oxidation state of the atoms in a sample: atoms that have different oxidation states contain different numbers of electrons (see Figure 1, above). This alters the value of their energy levels and therefore their XANES spectra

Image courtesy of M Blank: image source; Wikimedia Commons

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

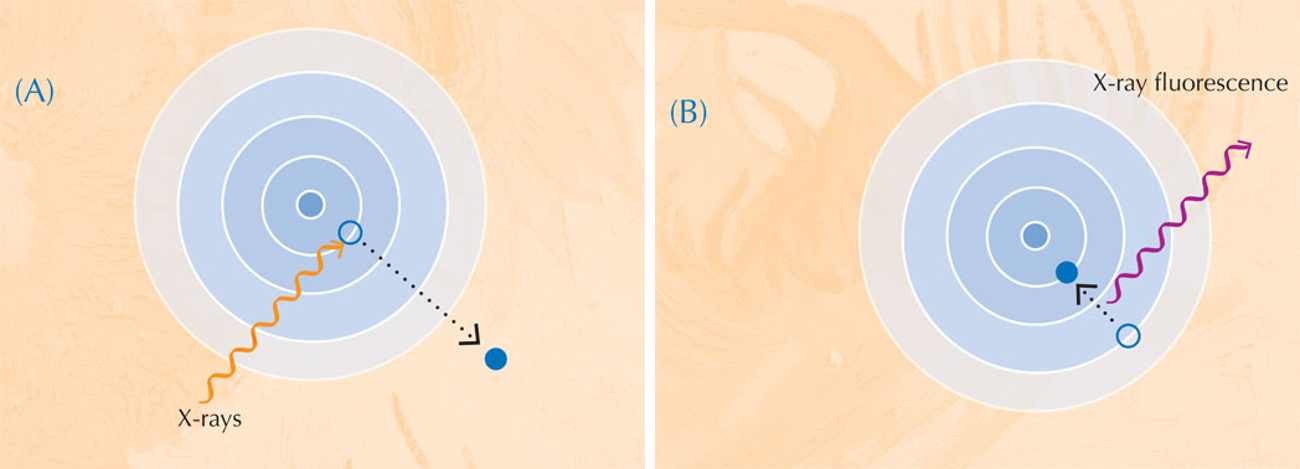

XRF

When they absorb X-rays, atoms enter an unstable excited state. When they then return to a more stable state, they emit secondary X-rays in a process called X-ray fluorescence (see Figure 5). The pattern of X-ray fluorescence (XRF) produced by a particular sample, called the XRF spectrum, can be used to map the distribution of elements across a given area. In contrast, XANES can only be performed on an isolated point in the sample. By combining the information obtained with both XRF and XANES, the authors were able to form a detailed picture of the chemistry of the paint samples.

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

Science in art

What do you and your students think? Should science be used to halt the degradation of important works of art, or even return them to their original state? Or should the ravages of time be accepted and even valued as historical evidence?

References

- Monico L et al. (2011) Degradation process of lead chromate in paintings by Vincent van Gogh studied by means of synchrotron X-ray spectromicroscopy and related methods. 2. Original paint layer samples. Analytical Chemistry 83: 1224-1231. doi: 10.1021/ac1025122

Web References

- w1 – The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) is an international research institute for cutting-edge science with photons. ESRF is a member of EIROforum, the publisher of Science in School. To learn more, visit: www.esrf.eu

- w2 – For more details of how synchrotron radiation is used in research, see:

- Capellas M, Cornuéjols D (2006) Shipwreck: science to the rescue! Science in School 1: 26-29.

- Capellas M (2007) Recovering Pompeii. Science in School 6: 14-19.

- w3 – To learn more about Vincent van Gogh and his art, visit the excellent website of the Van Gogh Museum: www.vangoghmuseum.nl

- A section of the museum’s website also contains primary- and secondary-school teaching resources: www.vangoghmuseum.nl/vgm/index.jsp?page=110&lang=en

- w4 – To listen to an interview with Koen Janssens talking about his research on van Gogh’s paintings, broadcast on BBC Radio 4, see: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00yjs49

- w5 – CLEAPSS is a UK advisory service providing support in science and technology teaching, on the subjects of health and safety; risk assessment; sources and use of chemicals; and living organisms and equipment. For more information, see: www.cleapss.org.uk

- For safety advice on using lead, chromium and their compounds, see the student safety sheets, which can be downloaded for free here: http://www.cleapss.org.uk/free-publications/general-publications

Resources

- Images and an animation of the investigation of the historic paint samples can be found at: www.vangogh.ua.ac.be

- To learn more about the science of preserving art, see:

- Leigh V (2009) The science of preserving art. Science in School 12: 70-75.

Institutions

Review

This article nicely links science with art and conservation studies. The sophisticated techniques used by the scientists reveal chemical changes in the pigments, which occur many decades after van Gogh’s paintings were finished.

The article is a useful way of demonstrating to students that there is always a scientific explanation for why artefacts change with time. It would be best used as a teaching aid in chemistry lessons and for students aged 16-18. The article could also be used to teach selected chemistry topics, such as oxidation and reduction.

To develop the students’ understanding of the chemistry behind the research, you could ask the following questions:

- The work of the scientists described in this article shows that sulphide ions may be the chemical species responsible for the reduction of chromium. Write down separate equations for the reduction of lead chromate (PbCrO4) by the sulphide-ion-containing compounds H2S and PbS. Hint: Cr(VI) compounds are oxidising agents.

- The scientists suggest that sulphate-containing compounds in the paint used by van Gogh may be a source of sulphide ions. Try to think of other ways in which paintings could be exposed to sulphide ions.

- Silver jewellery darkens over time when in contact with air. Write down the equation for the reaction responsible for this. Note that this is not a simple displacement reaction.

To show that lead chromate darkens when exposed to sulphide ions, you can demonstrate the following experiment in class:

- Synthesise lead chromate in a beaker by adding any water-soluble lead salt, such as lead(II) acetate, Pb(CH3COO)2, or lead(II) nitrate, Pb(NO3)2, to an equal volume of potassium chromate solution, K2CrO4. Dilute solutions (~ 0.03 M) will be sufficient.

- A yellow precipitate of lead chromate will form instantly. Filter off the residual liquid using a funnel and filter paper. In a fume hood, gently dry the precipitate with a blow dryer, ensuring that it does not dry completely.

- Prepare a dilute aqueous solution of hydrogen sulphide (H2S) by dissolving 50 mg sodium sulphide (Na2S) in 90 ml water. Add the resulting solution to 10 ml hydrochloric acid (HCl, 0.1 M). Stir the mixture.

- Fill a rubber balloon with air and connect it to a small glass Drechsel’s bottle containing a few millilitres of the dilute hydrogen sulphide solution (see image below). Aim the resulting stream of hydrogen-sulphide-gas-containing air onto the surface of the lead chromate precipitate.

- The precipitate will instantly turn brown. You have simulated and accelerated the darkening process observed in van Gogh’s paintings by many orders of magnitude.

Safety note: All soluble lead salts are toxic, and soluble chromates are toxic (above 0.003 M) and are suspected to be carcinogenic. Potassium chromate may cause sensitisation and / or ulcers after contact with the skin. There is limited evidence that lead chromate is carcinogenic. It may also cause harm to unborn children, so should not be used if the teacher or any of the students are, or may be, pregnant. Hydrogen sulphide is a toxic gas with a very unpleasant odour.

Perform the above experiment in a fume hood and wear safety goggles and gloves. Dispose of all chemicals according to your local safety regulations. See also the Science in School general safety note. You may find it helpful to consult the CLEAPSS student safety sheets on chromium and leadw5.

Vladimir Petruševski, Republic of Macedonia