Launching a dream: the first European student satellite in orbit Teach article

One hour and 34 minutes after the bright tail of the Kosmos 3M rocket disappeared from view, more than one hundred students are checking their watches nervously. The first signal from their satellite should arrive any minute. Barbara Warmbein, from the European Space Agency in Noordwijk, the…

In the mission’s ground-control centre in Aalborg, Denmark, students working as ‘mission control’ shift nervously in their chairs. The transformed university classroom is full of camera teams, cables have been secured to the floor with tape, and partitions display hastily pinned-up posters of the Student Space Exploration and Technology Initiative Express: SSETI Express. They don’t need fancy rows of monitors, buttons and levers or large screens along the wall, just a few tables, computers and a team of extremely excited students. Then, with a crackle and a beep, the radio comes on – SSETI Express is alive!

Photograph courtesy of J. Page

The first few chapters of the story – describing how hundreds of European students designed, built, tested and launched their own satellite to experience life as an engineer first-hand – read like a fairy-tale. Twenty-three universities from 14 different countries had teams working on SSETI Express – the ‘fast track’ satellite conceived by students who had had enough of theory and wanted to know what it was really like to launch a satellite.

They teamed up with the Education Department of the European Space Agency (ESA), and within 18 months had achieved what normally takes three to four years and costs a lot more than the €100 000 that went into SSETI Express. ESA provided the launch on the Russian rocket from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, and when the satellite blasted off on a crisp October morning in 2005 and sent its first signal back from orbit at a height of 690 kilometres, all signs pointed to a happy ending.

But that was where the fairy-tale ended and real life began. After a successful first day, contact to SSETI Express was lost: it could not recharge its batteries because of a failure in the electrical power system. The students tried to recover it – there was still a slight but significant chance. “Of course we are disappointed. But in a way this meets our educational objective,” says Neil Melville, Project Manager and System Engineer of SSETI Express. “We wanted to give students an idea of what it is like to launch a satellite, and troubleshooting is certainly an important part of it!”

in the cleanroom

Despite the disappointment of the power failure, Neil and the teams considered their mission a success. Two of the three miniature satellites on board SSETI Express were released, leading to some “stunningly perfect” results: the satellite passed over the observation point at exactly the planned orbit, and the timing of the first signal was exactly right. Ground control was able to talk to the satellite and it replied. Perhaps more importantly, the students learned useful and valuable lessons.

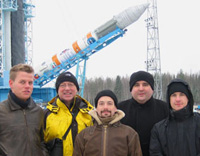

team watches the rocket

being erected

The majority of the students were studying for a degree in engineering. But because a project like SSETI Express also needs a legal background, there was also a team of law students – and if students of journalism hadn’t set up a public relations team, you might never have heard of the project at all. Discipline was not an issue: “We were all doing it of our own free will, and of course we were all extremely enthusiastic about it, so it was very easy to control because we all wanted it to happen,” explains Neil.

Their next satellite, the European Student Earth Orbiter or ESEO, is scheduled for launch in 2008, and the more ambitious students want to go even further: they are looking at ways to build and launch a Moon orbiter.

SSETI Express background

The SSETI Express mission started in December 2003, as a spin-off from the European Student Earth Orbiter (ESEO), because many of the students involved in the Student Space Exploration and Technology Initiative (SSETI) would graduate before their hardware would be anywhere near ready to fly. Its primary goal was to serve as a precursor mission to ESEO and to test some of the hardware already available for flight. The management and legal negotiations were performed by the Education Department of the European Space Agency (ESA).

The project boosted the motivation of all the students and experts involved – the new ‘express’ mission was a motivational aid, a technological test-bed, a logistical precursor, and, most importantly, a demonstration of capability to the SSETI and educational communities, the support network at ESA, and the space community in general. Its objectives were, apart from providing the all-important European networking and technology experience for the students, to deploy three miniature satellites, test student hardware, take pictures of the earth and involve the amateur radio community.

SSETI Express cost about €100 000. Although ESA paid for the central management, testing and transport, provided an expert technical review and facilitated the launch on the Russian launcher, the student teams found local funding for the satellite, its on-board experiments and most subsystems. The students had weekly meetings in a chatroom to discuss latest developments, configurations and problems, and only met in person during three workshops organised by ESA. All student teams had to have the approval of at least one professor at their university, but they did all the work themselves – quite a feat considering that parts for the satellite were built all over Europe and fitted perfectly when they were put together by the students at ESA’s Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands.

ESA and ESA education

The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the people of Europe. By coordinating the financial and intellectual resources of its 17 member states, ESA can undertake programmes and activities far beyond the scope of any single European country. ESA’s job is to establish and execute the European space plan. Its projects are designed to find out more about earth, its immediate space environment, the solar system and the universe, as well as to develop satellite-based technologies and promote European industries. ESA also works closely with space organisations outside Europe to share the benefits of space worldwide.

The ESA Education website is the focal point for information on space education programmes run by ESA’s Education Department and its partners. It offers links to, and free downloads of, various educational or supporting documents. There are still many differences between the national curricula of ESA’s member states, but several topics are taught at all levels of education in all countries. ESA’s Education Department has developed or adapted tools and courses for the various curricula with the help and knowledge of ESA experts, using results from space missions. Most courses fit many disciplines, including physics, geography, biology, mathematics, languages, sports or history.

Space, space travel, exploration and astronomy have always been multidisciplinary – this is why space is such a popular topic. Most of the ESA education projects are multidisciplinary, such as ideas for projects or competitions, and give new opportunities to the teacher at primary level, or to teams of teachers at secondary level. ESA also provides teacher training (for example, for new teaching tools or websites), organises workshops (e.g. Teach Space) and co-organises large-scale international events (e.g. Science on Stage). The aim is to bring teachers from all across Europe together and let them exchange their ideas on the best ways of teaching – not only space!

Institutions

Review

This article reports on a very exciting satellite project planned and performed by university students. It proves that students can be directly involved in aerospace technology, and will encourage both teachers and students of secondary schools to develop or join similar projects. The main problems are highlighted, to enable others to benefit from the experience gained.

Alesssandro Iscra, Italy