Revealing the secrets of permafrost Understand article

Studying permafrost enables us to look not only into the past, but also into the future. Miguel Ángel de Pablo, Miguel Ramos, Gonçalo Vieira and Antonio Molina explain.

Antarctica

Image courtesy of Miguel

Ángel de Pablo

Bracing themselves against the icy Antarctic wind, four bulky figures struggle uphill. Could they be penguins? Seals? No. They are permafrost scientists – well wrapped up against the cold, and laden with high-tech equipment.

This is how we spend about two months of each year before returning to our warm European laboratories to analyse our data. What are we doing and why do we do it?

What is permafrost?

distribution in the northern

hemisphere and in Antarctica,

showing boreholes used for

permafrost monitoring.

Click on image to enlarge

Image courtesy of Hugues

Lantuit, International

Permafrost Association

When winter arrives and the temperatures drop, ice forms on puddles or ponds. When the temperature stays below 0 °C for long enough, even the ground freezes. In some cases, the ground can remain continuously frozen for more than two years; we call this permafrost.

Clearly, this only happens in extreme environments: permafrost is found mostly around the poles and in high mountains (Figure 1). Nonetheless, in the northern hemisphere, where it has been most studied, permafrost covers 20% of the continental area.

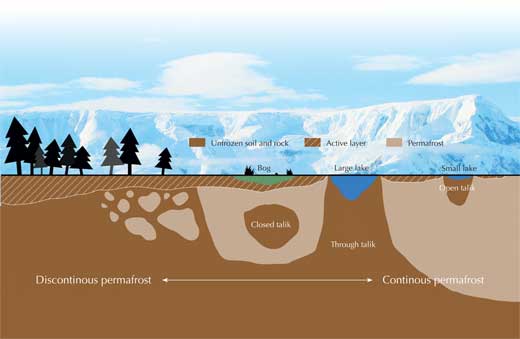

Mixed up with the permafrost may be patches of ground that remains unfrozen all year round (talik), the result of local pressure, high salinity or groundwater flow. This means that the permafrost may be spatially continuous, covering large regions, but can also be discontinuous or even patchy (Figure 1). The depth of the permafrost varies widely, depending on the environment: it can extend hundreds of metres into the ground, whereas on Deception Island in Antarctica, which is an active volcano, it is only 3 metres deep.

Modified image courtesy of PhysicalGeography.net; background image courtesy of Mark Sykes; image source: Flickr

Detecting permafrost

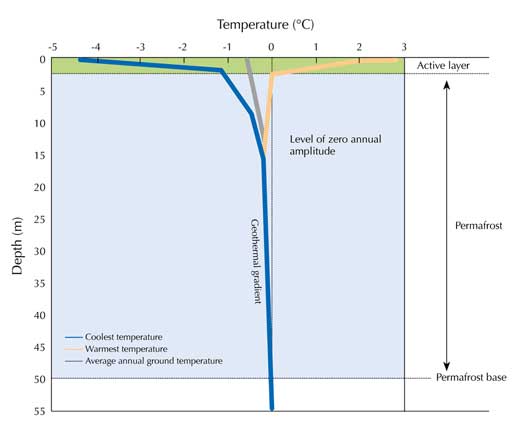

In theory, detecting permafrost is relatively easy: simply insert a thermometer into the ground and take regular measurements over two years. However, obtaining accurate and representative data is more complicated. This is because the ground’s most superficial layer is directly affected by solar radiation and weather conditions, so unlike the permafrost below, it thaws in the warm season.

formed by active layer

dynamics due to seasonal

freeze-thaw cycles

Image courtesy of Miguel

Ángel de Pablo

The surface layer above the permafrost is known as the active layer, and the repeating freeze-thaw cycles can cause it to form peculiar small-scale landforms such as polygonal terrains, stone circles and patterned ground.

These landforms, therefore, may indicate the presence of permafrost below. To check, we and other permafrost scientists drill boreholes and introduce temperature sensors at depths of as little as 50 centimetres or as much as 50 metres.

After several years of data logging, we can determine whether permafrost exists and what its thermal evolution was: how the ground temperature changed over the monitored period at different depths.

What can we learn from permafrost?

Why do we and other scientists want to know if the ground is frozen below the surface? Permafrost can be important in daily life, as well as telling us about the past and future climate on Earth; it can even teach us about other planets.

By measuring the temperature near the surface, we can see if the active layer is becoming thicker – as the permafrost below thaws – or thinner. This tells us how the climate is changing, as the thickness depends not only on air temperature, but also on factors such as snow cover. By monitoring the thickness of the active layer at different sites on Earth, we can investigate the influence of global warming on ground temperatures.

Image courtesy of Miguel Ángel de Pablo

Permafrost not only tells us about our current climate, but can also reveal our past climate. If a piece of rock warms up during the day, it will start to cool down the following night. However, it will remain warm for some time – especially deep in the rock, far from the surface where heat is being lost. Measuring temperatures at different depths inside the piece of rock can tell us about the rock’s previous thermal conditions. We can do the same in permafrost – the deeper we dig, the further we are travelling into the past.

collapse due to thawing ice-

rich permafrost terrain,

Alaska, USA

Image courtesy of Vladimir

Romanovsky, UAF

Soils and rocks, however, transfer heat at different speeds depending on their composition and structure; we call this thermal conductivity. If we know the thermal conductivity of the soil and rocks in the permafrost, we can convert depth into time, reconstructing climate evolution over the past decades or centuries. For example, finding colder rocks below the surface indicates that the climate at that depth (time) was colder than today. In theory, these calculations would also work in unfrozen ground but there, the geothermal gradient (the heat from the centre of Earth) also influences the temperature. In permafrost, the surface temperature plays a much more significant role.

Recently, scientists have discovered that changes in the active layer not only indicate climate change but can actually contribute to it. In the northern hemisphere, permafrost soils contain huge amounts of frozen organic matter. As global warming causes the active layer to thicken, this organic matter is exposed to decomposition by micro-organisms, releasing carbon dioxide and methane – important greenhouse gases – into the atmosphere, increasing the rate of global warming.

surface of Mars discovered

and analysed by the

Phoenix mission

Image courtesy of Phoenix /

ASU / JPL / NASA

Permafrost can also have a direct impact on humans, in areas where houses, roads and railways have been built on permafrost.

When the permafrost thaws, the ground resistance drops and constructions can collapsew1 (Figure 5). Increasing global temperatures will cause this to happen more frequently. By detecting permafrost below the surface, we can enable engineers to take precautionary measures to strengthen the constructions or not build them above permafrost in the first place.

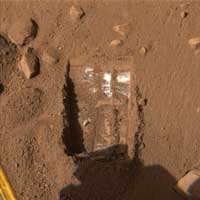

Finally, permafrost can help us to understand the dynamics of other planets, such as Mars. Mars has large amounts of frozen water forming permafrost (Figure 6), so studying the evolution of permafrost on Earth may help us to understand the past and present climate of Mars. Future permanent bases there may even use Martian permafrost as a source of water.

Studying permafrost in Antarctica

Miguel Ramos

For over two decades, our team has been conducting long-term permafrost research on different sites on Livingston and Deception Islands in the Antarctic Peninsula region. We measure the ground temperature both near the surface and inside boreholes as deep as 25 metres. We monitor the temperature in the ground, compare it with air and surface temperatures, and study the factors that affect ground temperature: from wind speed to rock properties such as thermal conductivity, porosity and humidity. We also measure the thickness of the active layer every year in the thaw season. Some of the boreholes have been monitored continuously for up to 25 years; others were drilled in the past six years.

We selected the Antarctic Peninsula region because:

in the Antarctic Peninsula

region.

Click on images to enlarge

Image courtesy of Benjamin

Dumas; image source: Flickr

- Most permafrost research is in the northern hemisphere, so we wanted to extend the monitored areas. Like our colleagues working in the north, we use international protocols for monitoring the active layer and measuring temperature inside the boreholes, as defined by the International Permafrost Association (IPA)w2.

- The peninsula is one of the few ice-free areas of the Antarctic – important because permafrost is stable if there is ice above it, and we wanted to investigate the active layer.

- It is close to the northern boundary of Antarctic permafrost, where ground temperatures are close to 0 ºC and the permafrost is therefore more sensitive to climate change.

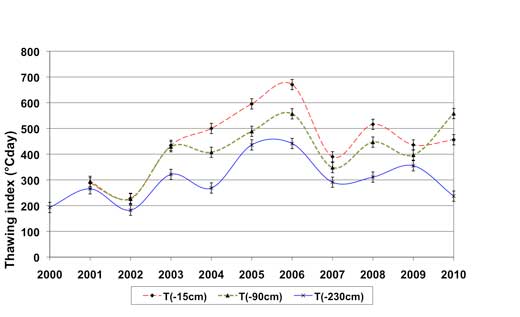

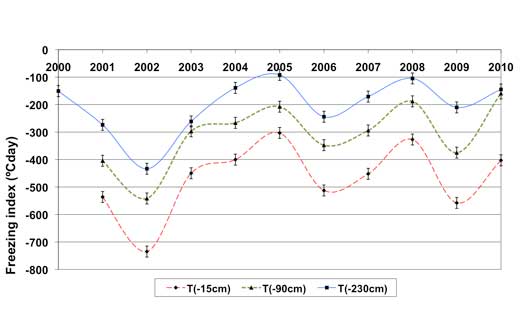

What do our data reveal? The main result is that although some areas that were previously permafrost are now unfrozen all year round, most of the ground on Livingston and Deception Islands is approximately as frozen as it was 10 years ago, despite global warming (Figure 8). These local differences are determined by the properties of the soil and rocks: material with higher thermal conductivity, for example, thaws more quickly. Over the next few decades, therefore, we expect permafrost with lower thermal conductivity to succumb to global warming, too. We hope to wrap up warm and return to Antarctica regularly to find out.

Figure 8: Patterns in freezing and thawing at three different depths in the Incinerador borehole (230 cm deep) on Livingston Island, between 2000 and 2010. Currently, we do not have enough spatial and temporal information to conclude that the permafrost in the Antarctic Peninsula is affected by global warming. In the Incinerador borehole, there is a slight positive trend in the thawing index, but the freezing index shows no change – overall, the permafrost is still stable.

Images courtesy of Miguel Ramos

Web References

- w1 – The US Public Broadcasting Service has developed an activity to make your own permafrost in class, build a house on it and observe the consequences of thawing. See: www.pbs.org/edens/denali/permawht.htm

- w2 – The International Permafrost Association co-ordinates international co-operation among scientists and engineers working on permafrost. See: www.ipa-permafrost.org

Resources

- The US National Snow and Ice Data Center runs an educational website on frozen ground, including many activities and resources on permafrost. See: http://nsidc.org/frozenground

- The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research offers a wealth of teaching resources on the Antarctic for students of all ages, in different languages, including dressing an Antarctic scientist in appropriate clothing. See: www.scar.org/about/capacitybuilding/antarcticeducation

- The United States Antarctic Museum has made lists of educational opportunities for teachers to experience the Antarctic and of resources for their students. See: www.usap.gov/usapgov/educationalResources.cfm?m=5

- To find some wonderful pictures of Antarctica to use in your lessons, visit: www.coolantarctica.com

- To learn about one school teacher’s trip to the Antarctic, see:

- Hayes (2007) Teaching on ice: an educational expedition to Antarctica. Science in School 6: 78-81.

- It is more than 25 years since a hole in the ozone layer was discovered over Antarctica. To find out what caused it and what the current situation is, see:

- Harrison T, Shallcross D (2010) A hole in the sky. Science in School17: 46-53.

Review

Many people know what permafrost is: frozen ground. But if researchers spend decades studying permafrost, there must be a lot more to know than just this simple information.

This article describes what permafrost is, how it can be researched, what can be learned from this research, and why the information revealed is valuable. Additionally, it contains information that could be used in the secondary-school science classroom for teaching many subjects and topics, including biology (e.g. ecology), environmental science (e.g. climate change), physics and chemistry (e.g. water and material properties), geology (e.g. rock properties) and meteorology (e.g. wind and temperature).

For lower-secondary-school students (ages 13-15), the article would be a good source of information about what permafrost is, how it is studied and what kind of important information it reveals. For upper-secondary-school students (ages 16-19), the article would also be helpful in understanding how everything that happens on the planet has direct or indirect implications that go far beyond what anyone can first imagine. For example, students will realise that global warming can negatively affect human land use and development.

Suitable comprehension and discussion questions include:

- What are the major differences between permafrost, talik and the active layer, with regard to properties and location?

- Which criteria are commonly used by researchers to locate permafrost sites?

- Explain how changes in the active layer can contribute to global warming.

- Why is it important to measure the temperature at different depths inside permafrost?

- A construction company plans to build houses in an area where permafrost exists. Would you support these plans? Explain your reasoning.

The article would be most appropriate for study in the countries of northern Europe as well as countries with very high mountains, as these countries are the ones that have permafrost. Nevertheless, because climate change, which affects and is affected by permafrost, is a global problem, this article can provide valuable information in any classroom, anywhere in the world.

Michalis Hadjimarcou, Cyprus