Seeing the light: monitoring fusion experiments Understand article

Finding out what is going on in the core of a fusion experiment at 100 million degrees Celsius is no easy matter, but there are clever ways to work it out.

experiment takes place is

shaped like a doughnut

Image courtesy of Pink

Sherbet Photography; image

source: Flickr

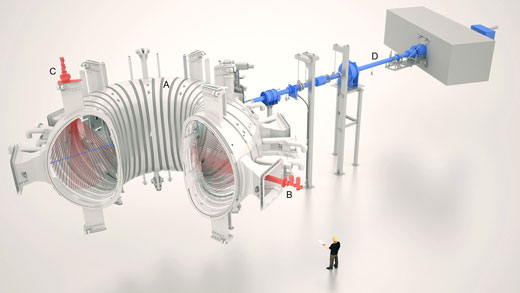

The Joint European Torus, JET, is the world’s largest nuclear fusion experiment, just outside Oxford in the UK. As described in a previous article (Rüth, 2012), our scientists are developing a clean energy source for the future, involving the fusion of light atoms in a doughnut-shaped vessel nearly six metres across.

This is not splitting the atom and there is no uranium involved – we fuse the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium into the heavier element helium. Forcing the atoms to fuse takes a huge amount of energy, but the fusion process itself releases yet more energy.

during a high-power pulse.

The plasma core is

transparent because the

hydrogen isotopes are

completely ionised, so

there are no electron

transitions providing

visible radiation – except

for a small visible wisp

of cooler plasma on the

inside lower edge

Image courtesy of EFDA-JET

Inside the experiment, the fuel (usually deuterium alone; the mixture with radioactive tritium is used only occasionally) is heated until the electrons are stripped off their nuclei. This ionised gas is called plasma and is the ideal environment for the collisions between nuclei that are required for fusion. The plasma is ten times hotter than the core of the Sun and races around the vessel, twisting and tumbling in an intricate magnetic cage woven by the scientists who control the machine.

Creating matter this hot is a major achievement, but keeping it confined long enough for a significant number of fusion reactions to happen is even more challenging – both because of the extremely turbulent nature of plasma this hot, and because of its tendency to pick up impurities from the components inside the vessel. Hence, sophisticated control mechanisms have been developed to monitor the plasma’s every facet during operation, make adjustments to keep it stable and clean where possible, or terminate it if it gets too turbulent (see EIROforum, 2012).

But how do we know what is going on inside this sealed vessel at 100 million degrees Celsius? Any measuring device that you tried to put into the plasma would be destroyed – sublimed into plasma in seconds. Even looking at the experiment through the sealed windows of the vessel is less informative than you might expect, as the hot plasma is almost transparent. This is because the core of the plasma is so hot that all the electrons have been stripped off their nuclei, so no electron transitions – the source of visible light – are possible.

However, there are many other ways to find out what is happening in the plasma. Our understanding of this jumble of high-speed particles comes from about one hundred diagnostics: cameras, sensors, detectors, lasers, ion beams and coils, to name a few. We will discuss some of these systems in this article.

Click on image to enlarge

Image courtesy of EFDA-JET

We have fusion! Gamma rays

The main product of a fusion reaction is fast neutrons. As well as measuring the number of neutrons, we always cross-check the number of fusion reactions with a second measure, the number of gamma rays.

works in a similar way to a

Geiger counter, shown

here. A Geiger counter is

used to measure various

forms of ionising

radiation, including gamma

rays

Image courtesy of Radioactive

Rosca; image source: Flickr

In addition to the main reaction between deuterium and tritium, during fusion, many other reactions occur in small proportions in the hot plasma, some of which leave the nuclei themselves in excited energy states. Just like electrons in excited energy levels, these nuclei then release their energy in the form of electromagnetic radiation. Because nuclear energy levels are very energetic, gamma rays are released rather than the visible or UV light emitted by electrons.

Gamma rays pass straight through most cameras, so a specialised detection system is needed. The experiment is surrounded by 2 m thick concrete walls to contain the radiation, but a long pipe channels some radiation through the walls to the detection laboratory. Here, we use a system similar to a Geiger counter, which generates an electric current when gamma rays pass through a small chamber, ionising the gas inside. We count the electrical pulses from two systems – one with a vertical view of the chamber, the other horizontal – which tells us how many fusion reactions have occurred, and where in the chamber they took place.

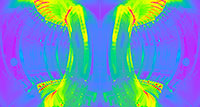

Measuring energy leakage: bolometry

One of the keys to a successful fusion experiment is confinement – preventing the energy from escaping from the plasma. Even if we keep the particles confined, significant amounts of energy can leak from the plasma in the form of electromagnetic radiation. Although it looks transparent, the plasma does give out a lot of radiation that we can’t see. To measure this radiation leakage, we need a device that, unlike our eyes, can see radiation at all wavelengths. We use a bolometer, which is surprisingly simple – just a tiny strip of metal. Electromagnetic radiation of any sort – e.g. radio waves, UV radiation or gamma rays – heats the metal, and changes its resistance, which is easily measured.

One of the main causes of the radiation is impurities in the plasma, most of which originate from the walls of the vessel. It is important to find out where the impurities end up – on the edge of the plasma is not a big problem, but impurities in the hot core will deplete energy from the most important area.

immensely hot plasma

away from the vessel wall.

These fields are many

times larger than those

of this bar magnet, made

visible by iron filings

Image courtesy of daynoir;

image source: Flickr

A single bolometer cannot distinguish between radiation from the core or the edge, but with a number of them, it is possible to build up a detailed 3D map of the radiation sources. This is achieved by putting each bolometer behind a couple of pinholes to narrow down their field of view. Then the results from all the different views – some through the middle, some just grazing the edge of the plasma, and so on – are combined with some clever processing to build up a 3D image. This construction of a 3D image from lots of individual measurements is a similar technique to that used in medical computed tomography (CT) scans, where a 3D image is compiled from many single X-rays taken from different angles.

Watching out for hot spots: cameras

vessel during an

experiment, showing hot

spots where the plasma is

touching the wall. Click on

image to enlarge

Image courtesy of EFDA-JET

It seems astonishing that a plasma at more than 100 million degrees Celsius can be contained within a metal vessel. Yet the huge magnetic fields created by the coils around JET succeed for the most part in keeping the plasma away from the vessel wall, which was recently refurbished with beryllium tiles that have a melting point of merely 1278 °C. One of the keys to the success of this set-up is an array of video cameras used to ensure that the plasma does not get too close to the vessel wall.

The indication that the plasma has moved too close is a hot spot on the wall, which gives out what is known as black body radiation. To the human eye, a hot spot would begin to glow red at around 500 °C, and would be orange by 1000 °C. However, it can be detected a lot earlier, because a hot spot will emit infrared radiation as soon as it becomes hotter than its surroundings.

Because most cameras can detect infrared radiation (using what is often called the night vision setting), a protection system has been developed that uses cameras to monitor for infrared hot spots. If one begins to develop, the plasma can be adjusted – for example by moving the magnetic field away from the wall or by turning down the power to reduce the temperature – before any damage is done.

Supporting activity: visualising infrared light

digital camera will register

the infrared radiation from

a TV remote control.

Bottom: Although visible

light from a torch is

absorbed by cola, infrared

radiation is not.

Click on images to enlarge

Images courtesy of EFDA-JET

Most cameras are sensitive in the infrared – even those in mobile phones. Shine a TV remote control at a camera and you can see the infrared radiation signalling its special code for the TV.

Next, show that the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation determines how well it can pass through a material – which is why we need different types of detector to monitor the different types of radiation emitted by the reactor. Shine a torch through a glass of cola: the visible light from the torch is absorbed by the drink, which still appears brown. Then shine the remote control through the cola while watching with the camera: the infrared light travels through the liquid more or less unaffected.

More about EFDA-JET

As a joint venture, the Joint European Torus (JET)w1 is collectively used by more than 40 European fusion laboratories. The European Fusion Development Agreement (EFDA) provides the platform to exploit JET, and more than 350 scientists and engineers from all over Europe currently contribute to the JET programme.

EFDA-JET is a member of EIROforumw2, the publisher of Science in School.

References

- EIROforum (2012) Bigger, faster, hotter. Science in School 24: 2-5.

- Rüth C (2012) Harnessing the power of the Sun: fusion reactors. Science in School 22: 42-48.

Web References

- w1 – More information is available on the EFDA-JET website.

- w2 – EIROforum is a collaboration between eight of Europe’s largest inter-governmental scientific research organisations, which combine their resources, facilities and expertise to support European science in reaching its full potential. As part of its education and outreach activities, EIROforum publishes Science in School.

Resources

- Warrick C (2006) Fusion – ace in the energy pack? Science in School 1: 52-55.

- For an introduction to the electromagnetic spectrum and how it is used in astronomy, see:

- Mignone C, Barnes R (2011) More than meets the eye: the electromagnetic spectrum. Science in School 20: 51-59.

Institutions

Review

Following on from a previous article (Rüth, 2012), this article gives a clear picture of some of the wealth of detectors used in nuclear fusion research. Teachers can use this article to provide information about how fusion can be monitored, and what difficulties and challenges scientists face when working at such high temperatures.

Suitable comprehension and discussion questions include:

- Why is a high amount of energy required for fusion to occur?

- What type of material has to be used for the chamber walls? Why?

- Which devices are used to monitor what is happening inside the plasma?

- How is the plasma confined within the walls and kept at a safe distance from them?

- How can leakage of energy be detected?

The discussion with students could then be taken further by addressing environmental impacts, sustainability and the importance of such experiments.

Catherine Cutajar, Malta