Science is cool… supercool Understand article

When we cool something below its freezing point, it solidifies – at least, that’s what we expect. Tobias Schülli investigates why this is not always the case.

iStockphoto

How is it possible that clouds at high altitude, at a temperature lower than 0 °C, consist of tiny droplets of water instead of ice? Actually, under certain conditions, liquids can remain liquid well below their melting point. Although this phenomenon, known as supercooling, was discovered in 1724 by Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (Fahrenheit, 1724), it is still the subject of much research.

The different states of matter

For scientists, the liquid phase is a curious state of matter between order and disorder. The disordered state of matter is well illustrated by the perfect gas: the thermal movement of the individual atoms (or molecules) is so important that the attractive forces between them play no role and they move freely through space. At the other extreme, in the solid state, every atom remains at a fixed site, tightly bound to its neighbours. Driven by the optimisation of chemical bonds and binding energies, this generally leads to the densest packing of the atoms, in a repeated three-dimensional arrangement, which is called a crystal. Therefore, what we call a solid is in fact, most of the time, a crystalline solid.

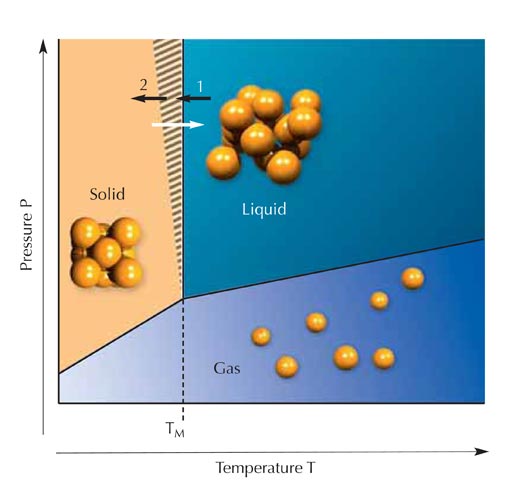

In the liquid – intermediate – state, the neighbouring atoms touch each other as in the solid state (both states are thus referred to as condensed matter), but the individual atoms can migrate around, inhibiting the formation of the perfect regular pattern of a crystal. The density of a liquid (compared to a gas) thus differs very little from that of the solid state (see Figure 1).

The states of matter:

a) In the solid or crystalline state of matter, each atom remains at a fixed site. It can be considered to be tightly bonded to its neighbours. If we heat a crystal, the atoms begin to move (thermal vibration).

b) In the liquid state (at temperatures above the melting point), thermal movement allows the individual atoms to move around freely, although the attractive forces between the atoms ensure that they are almost as close together as in the solid state. A liquid therefore has almost the same density as a solid, and resists compression as does a solid.

c) At elevated temperatures, the thermal movement of the individual atoms in a gas becomes so important that the attractive forces between the atoms no longer play a role and the atoms can move freely through space. The density of a gas depends on the surrounding pressure and temperature. At high pressure or low temperature, the atoms may start to stick together again and condense into denser arrangements to form a liquid or a solid. For this reason, these two states are also called condensed matter

Image courtesy of Tobias Schülli

Image courtesy of Tobias Schülli

a metastable state: it will

remain in this state only if

the conditions remain

unchanged. The blue circle is

in a transition (or unstable)

state, moving towards the

stable state represented by

the black circle. Any unstable

state will move towards the

stable state, whereas the

metastable state requires

specific conditions to do the

same

Image courtesy of Tobias

Schülli

Although a liquid is considered to be mainly disordered, atoms may arrange themselves locally in small clusters, giving rise to the notion of local order. The exact nature of these states of local order is very difficult to observe experimentally, but is believed to play a crucial role in the transition of a substance from a disordered phase to an ordered one.

Whether a particular substance is in the gaseous, solid or liquid phase depends on the temperature and pressure. Ice at atmospheric pressure will melt at 0 °C, mercury at -39 °C and gold at 1064 °C. As they get warmer, solids (crystals) melt at exactly these temperatures. However, the opposite is not true: when a liquid is cooled to its melting point, the formation of a crystal is possible but does not necessarily happen at exactly the melting point (Figure 2). In the striped area of the figure, a pure liquid (with no crystalline impurities) will remain liquid. We say that the liquid is supercooled. This state of matter is said to be metastable (Figure 3).

How can we explain supercooling?

The first explanation of supercooling lies in the physics of crystallisation. The formation of a crystal requires a nucleus of regularly arranged atoms, around which the crystal can grow. Crystallisation most commonly occurs when the liquid is in contact with a solid surface or when the liquid contains crystalline impurities; it is as if the liquid mimics the ordered structure of the neighbouring surface. This is called heterogeneous nucleation, starting from a seed.

In the absence of a crystalline solid, the spontaneous formation of a large and regular structure from the disordered liquid is unlikely. Although small numbers of atoms may spontaneously form a regular arrangement, these clusters are usually too small to serve as crystallisation nuclei, and quickly re-dissolve in the liquid. A pure liquid, therefore, needs to be significantly supercooled before homogeneous nucleation occurs: a few atoms in the liquid spontaneously order in the right manner to form a crystal that is large and stable enough to serve as the nucleus for further crystal growth (Figure 4).

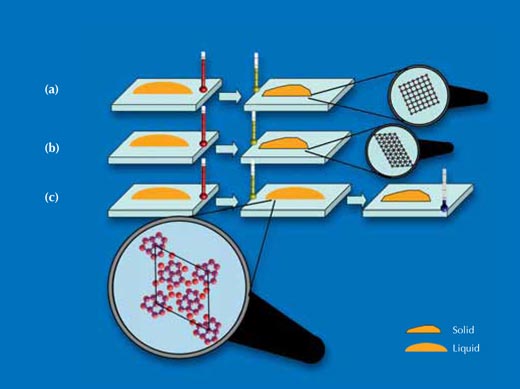

a) Crystal formation usually begins around an already crystalline solid in contact with the liquid (heterogeneous nucleation).

b) As a consequence, the liquid needs to be significantly supercooled before homogeneous nucleation occurs: a few atoms in the liquid spontaneously order in the right manner to form a crystal, which then serves as the nucleus for further crystal growth

Image courtesy of Tobias Schülli

Most of the tiny droplets of water which constitute stratiform and cumulus clouds do not contain any seed crystals; these droplets can remain liquid well below 0 °C.

Deep supercooling in metals

Even more spectacular than water, which can be supercooled only about 40 degrees below its melting point of 0 °C, are metals, which can exist as liquids at several hundred degrees below their melting point. This is known as deep supercooling and has challenged scientists to go beyond the crystal nucleation theory to explain the metastability of liquids (Turnbull, 1952).

Scientists have speculated that the internal structure of some liquids could be incompatible with crystallisation. In the 1950s, Frederick Charles Frank suggested that the densest arrangement of a small number of atoms may be different to the local arrangement of atoms in a crystal, and that these clusters in a liquid are therefore ordered in the wrong way to serve as a crystallisation nucleus (Frank, 1952).

Image courtesy of Nicola Graf

structures that are not

compatible with the

formation of a crystal:

(a) An icosahedron, the

densest arrangement

possible for 13 atoms.

(b) A cluster of 7 atoms

with pentagonal symmetry.

Images courtesy of Tobias

Schülli

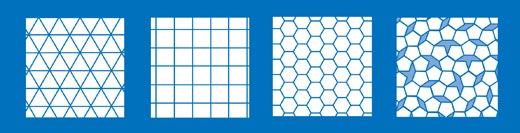

As a model, Frank used the icosahedron: a central atom with twelve surrounding atoms. Such a structure, which has a pentagonal symmetry, cannot form the basis of a crystal. Generally, a crystalline structure has to repeat in three dimensions, like bricks in a wall. A cubic arrangement, for example, is an excellent structure for a crystal, as it is both dense and perfectly regular.

Using a two-dimensional comparison, triangles, rectangles or hexagons can fill a plane perfectly, whereas pentagons cannot (Figure 5). In three dimensions, pentagonal structures are incompatible with the formation of a crystal (Figure 6).

Recent simulations and theoretical models support Frank’s idea, suggesting that a significant fraction of the atoms in liquids arrange themselves in clusters with five-fold symmetry, thus presenting an obstacle to crystallisation. So far, however, very few experiments have allowed the visualisation of pentagonal symmetry in liquids (Reichert et al., 2000).

Supercooling in semiconductor nanostructures

My own encounter with the phenomenon of supercooling was not really intentional. Actually, the focus of my research, within a team at the CEAw1 in Grenoble, France, was to understand and improve novel growth methods for semiconductor nanostructures. In these methods, the processes of solidification and nucleation are crucial. The attention of our team was attracted by a report on supercooling in droplets of metal–semiconductor alloys: these droplets offered us a good system to study the influence of a crystalline seed (a silicon surface) on the solidification of the alloy.

We deposited tiny droplets (0.1-0.2 µm) of a liquid gold–silicon alloy on a silicon surface, prepared under ultra-high vacuum conditions, a standard technique used in semiconductor processing. We observed that, while in contact with this crystalline surface, the droplets remained liquid at 240 °C, well below their melting point (which is 363 °C). To understand this extraordinary supercooling behaviour (usually only observed in the absence of crystalline seeds), we carried out an experiment at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF)w2, also in Grenoble. The scattering of very intense X-rays produced in a synchrotron is a unique way to obtain information about the arrangement of atoms in a liquid and on solid surfaces.

We fired X-rays almost parallel to the surface of the silicon crystal on which the droplets of gold–silicon alloy had been deposited. At an angle of only 0.1° (a technique called grazing incidence), the X-rays are reflected by the flat silicon surface and penetrate the droplets deposited on it. The scattered X-rays carry information about the atomic arrangement of the last atomic layer of the silicon surface, as well as on the structure of the droplets.

These experiments allowed us to determine the state (liquid or crystalline) of the droplets as they were cooled, and to determine the exact atomic arrangement of the upper atomic layer of the silicon surface. The X-ray results showed that in the uppermost atomic layer of the silicon surface, the atoms were arranged with five-fold symmetry. On these surfaces, even when cooled to more than 100 degrees below their melting point, the droplets remained liquid.

A more detailed analysis of the solid / liquid interface revealed that these pentagonal surface structures were formed from a single layer of gold atoms bonded tightly to the silicon crystal. As explained before, we generally expect liquids to mimic the solid structure with which they are in contact, provoking heterogeneous nucleation. Our measurements showed that such mimicking of the surface structure takes place, but that it can have the opposite effect: a structure that is incompatible with the formation of a 3D crystal can force the liquid to locally adopt the ‘wrong’ type of order. Instead of triggering heterogeneous nucleation, this increases the stability of the supercooled phase of the liquid (see Figure 7).

After 60 years of research into supercooling of metals, this is finally the experimental demonstration that five-fold symmetry affects the metastability of a liquid (Schülli et al., 2010; Greer, 2010).

(a) When the silicon crystal was cut along the cubic facets, the silicon atoms at the surface that was in contact with the droplet were arranged in a square lattice. On this surface, the droplets crystallised at about 60 K below their melting point. X-ray results showed that the droplet had crystallised in a structure and orientation similar to the silicon crystal on which it sat.

(b) When the silicon crystal was cut in the spatial diagonal of the cube, the silicon atoms at the surface that was in contact with the droplet were arranged in a triangular lattice. The droplet on this surface crystallised at about 70 K below its melting point. X-ray results showed that the droplet too had crystallised in a structure and orientation similar to the silicon crystal on which it sat.

(c) The silicon crystal was cut as in b) but underwent a special treatment at high temperature that provoked the formation of a pentagonal atomic arrangement of gold atoms bonded to the silicon surface. On this surface, the droplets remained in their metastable liquid phase down to 120 K below the melting point – deeply supercooled.

Image courtesy of Tobias Schülli

Experiment with supercooling

Place an unopened bottle of still mineral water in the freezer for 1–2 hours. After this time, the water should be around -10 to -5 °C. Because the water should have no solid impurities in it, it should still be liquid even at this temperature – it is supercooled.

Carefully remove the bottle from the freezer, then hit it on the table or with your hand. You should be able to see that the water crystallises (freezes), with the ice formation progressing very quickly through the whole bottle. The crystallisation is triggered by the shock wave travelling through the liquid. (The shock wave is another possible explanation of why aeroplanes leave a visible trail of water crystals behind them.)

This can only be achieved in liquids that do not contain seeds that may provoke crystallisation. It is unlikely to work with tap water, which may contain crystalline impurities that trigger crystallisation closer to the melting (freezing) point of water.

Note: do not leave the bottle in the freezer for too long, because once the water gets below -10 to -5 °C, it will freeze, even if there are no crystalline impurities.

References

- Fahrenheit DG (1724) Experimenta & observationes de congelatione aquæ in vacuo factæ. Philosophical Transactions 33: 78-84. doi: 10.1098/rstl.1724.0016

- Frank FC (1952) Supercooling of liquids. Proceedings of the Royal Society 215: 43-46. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1952.0194

- Greer AL (2010) Materials science: a cloak of liquidity. Nature 464: 1137-1138. doi: 10.1038/4641137a

- Download the article free of charge here, or subscribe to Nature today: www.nature.com/subscribe.

- Reichert H et al. (2000) Observation of five-fold local symmetry in liquid lead. Nature 408: 839-841. doi: 10.1038/35048537

- Download the article free of charge here, or subscribe to Nature today: www.nature.com/subscribe.

- Schülli TU et al. (2010) Substrate enhanced supercooling in AuSi eutectic droplets. Nature 464: 1174-1177. doi: 10.1038/nature08986

- Download the article free of charge here, or subscribe to Nature today: www.nature.com/subscribe.

- Turnbull D (1952) Kinetics of solidification of supercooled liquid mercury droplets. Journal of Chemical Physics 20: 411-424. doi: 10.1063/1.1700435

Web References

- w1 – The CEA is the French Atomic Energy and Alternative Energies Commission (Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives). To learn more, see: www.cea.fr

- w2 – The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) is an international research institute for cutting-edge science with photons. ESRF is a member of EIROforum, the publisher of Science in School. To learn more, visit: www.esrf.eu

Resources

- For a further consideration of clouds, see:

- Ranero Celius K (2010) Clouds: puzzling pieces of climate. Science in School 17: 54-59. www.scienceinschool.org/2010/issue17/clouds

Institutions

Review

One of nature’s strange phenomena is that, for some substances, the melting point is not always the same as the freezing point. In this article, Tobias Schülli leads us into the world of condensed matter; he introduces the differences between the states of matter, and provides an explanation of this apparent anomaly: supercooling.

The article can be used in various ways as a teaching aid. Teachers could get their students to read the article and then initiate a classroom discussion, not only about changes in states of matter but also about modern research methods in the field of condensed matter physics. To ensure that the students had understood the text, the teacher could question them, for example about conditions of crystal growth.

The article could also inspire some readers to develop their own educational material on the topic of supercooling.

Furthermore, the simple classroom activity in the article may demonstrate to students that it is not only temperature that determines the state of matter.

Vangelis Koltsakis, Greece