Maggie Aderin-Pocock: a career in space Understand article

As a child, Maggie Aderin-Pocock dreamed of going into space. She hasn’t quite managed it yet, but she’s got pretty close, as she tells Eleanor Hayes.

(left) and infrared light (right

and centre)

Image courtesy of ESO /

University of Oxford / LN

Fletcher / T Barry

Are you ready for a tour of the Universe? Strap on your helmet and we’ll dim the lights.

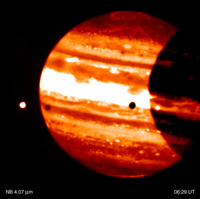

Jupiter with its moon Io (left

in this image), taken with

ESO’s Very Large Telescope

Image courtesy of ESO

Over the course of the next hour, we’ll be travelling far across the Solar System, across our galaxy and even beyond. As we leave Earth behind us, we’ll look back and marvel at our own planet and its watery surface before whizzing off to orbit the Moon and see how very different it is. Then we’ll take a trip to the centre of the Solar System and examine the Sun before visiting Venus, Mars and Jupiter. We’ll take a close look at the rings of Saturn before ending up on Pluto. From there, we’ll leave the Solar System behind us and visit some of the other stars in the night sky, until we reach the very edge of our galaxy. There, we’ll use the latest technology on board the Hubble space telescope to see what’s at the end of the Universe and try to calculate how many galaxies there are, and the probability of there being life out there.

All set for take-off? 3-2-1 and we’re off!

This may sound like fantasy, like a once-in-a-lifetime dream, but Maggie Aderin-Pocock has taken this tour regularly over the past five years, guiding children as young as four years old through the wonders of our Universe. From the safety of their classroom, they are whirled away on a simulated journey through space and time, transported only by an interactive computer programmew1 and Maggie’s boundless enthusiasm.

Image courtesy of Paul Nathan

Space scientist Maggie has many demands on her time – developing instruments for space satellites, filming with the BBC and, since March 2010, looking after her daughter Laurie. But she still makes time to visit schools around the UK.

“I like to have aspects in my talk that will appeal to girls and aspects that will appeal to ethnic minorities, but the main challenge is trying to get people to realise that science is for everybody. Anyone who’s inquisitive is effectively a scientist – you don’t have to have a bowtie or mad hair.

“I also try to show that if you look back in history, all cultures have been interested in astronomy. I talk about Stonehengew2 in the UK and about a stone circle in southern Egypt – Nabta Playaw3, one of the oldest stone circles in the world, from about 6000 BC. Both are ancient astronomical constructions, which show that people across the world have looked up at the night sky and wondered what’s out therew4.”

stone circle that allowed

celestial events to be

predicted

Image courtesy of Old

Moonraker image source:

Wikimedia Commons

What advice does Maggie offer the young scientists she meets on her school visits?

“My advice is to find out what you’re really interested in and pursue that, but to be aware of other scientific areas, too. As scientists, we can be very linear, pursuing one course of research in great detail, but by looking around you may find other fields of science that can enhance your research. Some of the greatest insights and the greatest scientific discoveries will be made where the sciences overlap.”

Nobody could accuse Maggie of having had a linear career. As a young child, she was captivated by a library book with an astronaut on the front cover and dreamed of being an astronaut too – but her route into space science was anything but direct.

“I suffer from dyslexia, so I wasn’t very good at English or history at school, but I did have an aptitude for science. My father was keen on my studying medicine and I found biology absolutely fascinating, but I decided in the end to study physics.” As a student in London, UK, Maggie built her own telescope and began to specialise in optics. Sponsored by major oil companies, she then did a PhD, developing an optical system for looking at engine oils, to enable lubricants to be tested more effectively and cheaply – a system that is still used commercially, more than 15 years later.

When Maggie entered the job market in 1994 after her PhD, Britain was in the middle of a recession and jobs were hard to find. With some qualms, she took a job at the UK Ministry of Defence. “As a child, I was a pacifist, but my ideas had evolved since then and I had realised that we need some defence. However, during the interview I was told ‘we can’t tell you what you’ll be doing until you sign the Official Secrets Act’. So I turned up knowing that there might be some things I wasn’t prepared to do, and that I might have to leave the job before I really started.”

As it turned out, Maggie hugely enjoyed her work, developing optical systems that detected missiles, warned the pilot and sent out decoys to prevent the plane being hit. “Most of the work I’d done for my PhD had been lab-based and suddenly I was flying around pointing cameras out of the open door of an aircraft. “It was more like being James Bond than a scientist!”

South Telescope, reflecting

the Chilean sunset

Image courtesy of Gemini

Observatory / Keith Raybould

Her next project involved developing hand-held land-mine detectors, which relied on a metal detector, ground-penetrator radar (to trace the rough outline) and nuclear quadropole resonance (to detect explosives). “Land-mine detectors were a very topical subject in the late 1990s because of all the work Princess Diana was doing. For that reason, we got a lot of visits from politicians and I used to try to find interesting ways to tell them about the technology – and that’s when I started to think about doing public engagement work.”

Milky Way, as observed in the

near-infrared with the NACO

instrument on ESO’s Very

Large Telescope

Image courtesy of ESO / S

Gillessen et al.

At that point, though, Maggie’s career took another turn. “I’d always wanted to work in space and astronomy and in 1999, a job came up at University College London, managing a project making bHROSw5, an optical spectrograph for the Gemini Telescope in Chile.” In fact, the job turned out to be a lot more than project management.

“I like project management but I really love the hands-on stuff too. At the end of the project, we packed the instrument into 28 boxes and I flew out to Chile myself to construct it at the telescope. Chile is my favourite place on earth: because it’s in the southern hemisphere, you can look up into the night sky, right into the heart of the Milky Way. I stayed out there for about nine months. In the end, my husband had to come out and bring me home!”

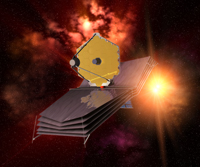

On her return to the UK in 2004, Maggie moved from building instruments for peering into space to building instruments that actually travel into space. As a project manager at Surrey Satellitesw6 (now part of Astrium), she was responsible for the development of a spectrographic instrument, one small component of the vast James Webb Space Telescopew7. A collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA)w8 and the Canadian Space Agency, the James Webb Space Telescope will replace the Hubble Space Telescope and is due to be launched in 2018.

“As a child, I wanted to be an astronaut. I haven’t succeeded in doing that (yet!) but being a space scientist is the next best thing because I’m building instruments that go into space. When the telescope is launched, it’s going to travel a million miles from Earth and look across the Universe, hopefully giving us a new understanding of what’s out there. Being part of such an epic project fills me with joy.”

James Webb Space Telescope,

due to be launched in 2018

Image courtesy of TRW and

Ball Aerospace

Subsequently, Maggie worked for Astrium on several optical instrumentation projects for ESA and NASA and for ground-based telescopes. Her latest project involved detecting carbon dioxide, as part of a large NASA project. “It’s quite challenging. We can detect the absorption characteristics of carbon dioxide, but what we really want to do is to localise the emission of carbon dioxide – to find out where it’s coming from and how much there is, so that in future people who release carbon dioxide are taxed for it. Doing that from space makes a lot of sense, but you need to develop very high-resolution detectors.”

It was while working for Astrium that Maggie became increasingly involved in science communication. In 2006, with funding from the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Councilw9, she started visiting schools and appearing on television – on a news programme. “I wanted to demonstrate parabolic flight by throwing an apple, but the news crew were a bit perturbed because you don’t usually do live demonstrations on the news. In the end, they loved it and I’ve been asked to do other news programmes since – and I always bring a demonstration if I canw10.”

eclipse of the Sun occurs

Image courtesy of Paul Nathan

Since the birth of her daughter Laurie, Maggie has been taking a break from space instrumentation, but she’s still very involved in science communication. “Four days after Laurie was born, I got an email asking me to make a documentary for the BBC. My husband took time off work to look after her and we travelled the world making a documentary called ‘Do we really need the Moon?’. Right now, we’re filming a second documentary about why we need satellites, and Laurie’s travelling with us.”

When Laurie is a bit older, Maggie plans to return to space instrumentation, but in the meantime she’s hoping to be involved in a project for music and literary festivals, looking at the science in Shakespeare’s plays. “For instance, in Romeo and Juliet, Juliet drinks a potion that makes her appear dead. What was the chemical composition of that potion? Does it really exist? Or when Shakespeare’s characters navigate by the stars, which constellations were they using? We can use the plays to see how science has evolved since the 17th century.”

Clearly, Maggie does not regret her choice of career. “I’m very lucky to have found work I enjoy so much and that is also so varied – not just building equipment that goes into space but also talking about it. I like to pass on my enthusiasm when I can.”

Web References

- w1 – Celestia is a free, interactive, 3D astronomy programme that allows you to travel throughout the Solar System, to any of more than 100 000 stars, and even beyond our galaxy. Devise your own tour of the Universe or take tours prepared by other users. See: www.shatters.net/celestia

- w2 – Stonehenge near Salisbury, UK, is an enormous stone circle constructed between 3000 and 2000 BC. Archaeologists disagree about the religious significance of the monument, but its design appears to have allowed eclipses, solstices, equinoxes and other celestial events to be predicted. To learn more, see: www.stonehenge.co.uk

- To find out more about the 2008 excavation of Stonehenge and for a 360° panorama of the stone circle, visit the BBC website (www.bbc.co.uk) or use the direct link: http://tinyurl.com/55qv67

- w3 – To learn more about Late Neolithic astronomy at Nabta Playa, see: www.colorado.edu/APS/landscapes/nabta or use the shorter link: http://tinyurl.com/7pghhsu

- w4 – Aimed at young children, Stories of Stars is a collection of myths about astronomy, each short story taken from a different culture. To download the illustrated stories (in English, Aragonese, French, Portuguese and Spanish), visit: http://sac.csic.es/unawe/cuentos_cuentos_de_estrellas_eng.html or use the shorter link: http://tinyurl.com/75z92gj

- w5 – bHROS is an optical spectrograph, part of the Gemini South Observatory in Cerro Pachón, Chile. To learn more, see the Gemini Observatory website (www.gemini.edu) or use the direct link: http://tinyurl.com/7wwbj7w

- w6 – Formed as a spin-off company by the University of Surrey, UK, Surrey Satellite Technology specialises in designing, building and launching small satellites. See: www.sstl.co.uk

- w7 – The James Webb Space Telescope will be a large infrared telescope, examining every phase of cosmic history from the first glow after the Big Bang to the formation of galaxies, stars and planets, to the evolution of the Solar System. See: www.jwst.nasa.gov

- w8 – ESA is Europe’s gateway to space, organising programmes to find out more about Earth, its immediate space environment, our Solar System and the Universe, as well as to co-operate in the human exploration of space, develop satellite-based technologies and services, and to promote European industries. See: www.esa.int

- ESA is a member of EIROforumw11, the publisher of Science in School.

- w9 – The Science and Technology Facilities Council carries out civil research in science and engineering, and funds UK research in areas including particle physics, nuclear physics, space science and astronomy. See: www.stfc.ac.uk

- w10 – For a video of Maggie explaining to Newsnight’s Jeremy Paxman why the Moon looks blood red during a lunar eclipse, see: www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13787011 or use the shorter link: http://tinyurl.com/7v6vxxy

- w11 – EIROforum is a collaboration between eight of Europe’s largest inter-governmental scientific research organisations, which combine their resources, facilities and expertise to support European science in reaching its full potential. As part of its education and outreach activities, EIROforum publishes Science in School. To learn more, see: www.eiroforum.org

Resources

- The Celestia Motherlode website offers 12 detailed educational space tours to more than 400 destinations, with student worksheets to complete. See: www.celestiamotherlode.net/catalog/educational.php

- The European Southern Observatory (ESO) is the foremost inter-governmental astronomy organisation in Europe and the world’s most productive astronomical observatory. Its website offers a wealth of news, images, videos and other material about astronomy, space and the Universe, aimed at schools and the public. See: www.eso.org

- ESO is a member of EIROforumw11, the publisher of Science in School.

Review

This is a very interesting article about the fabulous and dynamic life of a modern-day scientist. It may best be linked to the physical sciences, but it can also be used very easily in a multidisciplinary context.

It shows how important it is for us teachers to inspire our students to imagine and dream. I feel that as science teachers, we should provide a fertile environment for them to do so; we should provide situations and information that evoke students’ interest while helping them to base their dreams on facts rather than fiction.

This article is very suitable for discussions, for example, on possible careers in science, on scientists as real people, on the characteristics and traits of scientists and on women in science. It can also be used to illustrate how scientific principles and concepts can be linked to countless applications around us.

I hope that Maggie will someday manage to go into space and that all our students fulfil their dreams.

Paul Xuereb, University Junior College, Malta