The LHC: a step closer to the Big Bang Understand article

On 10 September 2008 at 10:28 am, the world’s largest particle accelerator – the Large Hadron Collider – was switched on. But why? In the first of two articles, Rolf Landua from CERN and Marlene Rau from EMBL investigate the big unresolved questions of particle physics and what the LHC can…

Image courtesy of CERN

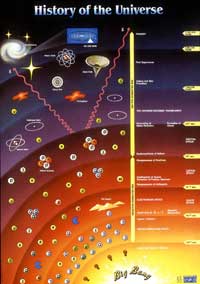

When the Universe was formed 13 700 million years ago in the Big Bang, an immense concentration of energy was transformed into matter within less than a billionth of a second. The temperatures, densities and energies involved were extremely high. According to Einstein’s law E=mc2, to create a matter particle of a certain mass (m), you need a corresponding amount of energy (E), with the speed of light (c) defining the exchange rate of the transformation. So the high energies shortly after the Big Bang could have created particles of very large mass. Physicists have proposed these hypothetical heavy particles to explain open questions about the creation and composition of our Universe.

To investigate these theories, scientists have built the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). If a type of particle can be created in the LHC, the world’s largest particle accelerator, then it is assumed to have existed shortly after the Big Bang. The LHC will collide particles using the highest kinetic energies that are currently technically possible (these energies correspond to those that are calculated to have existed 10-12 seconds after the Big Bang), crashing the particles into each other with close to the speed of light. This should result in new particles of higher mass than any previous experiments have achieved, allowing the physicists to test their ideas. Despite suggestions by the media, however, the energy of collisions in the LHC will be about 1075 times lower than in the Big Bang, so fears that a ‘Small Bang’ could be recreated are unfounded.

The building blocks of matter: the standard model

Since the days of the Greek philosophers, people have wondered what our world is made of. Is it possible to explain the enormous diversity of natural phenomena – rocks, plants, animals (including humans), clouds, thunderstorms, stars, planets and much more – in a simple way? The theories and discoveries of physicists over the past century have given us an answer: everything in the Universe is made from a small number of building blocks called matter particles, governed by four fundamental forces. Our best understanding of how these are related to each other is encapsulated in the standard model of particles and forces (see image). Developed in the early 1970s, it is now a well-tested theory of physics.

physics.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

Matter particles come in two different types: leptons and quarks. Both are point-like (no bigger than 10-19 m, a billion times smaller than an atomic diameter). Together, they form a set of twelve particles, divided into three families, each consisting of two leptons and two quarks. The fundamental family, consisting of an up-quark, a down-quark, an electron and a neutrino (the two leptons) is sufficient to explain our visible world. The eight matter particles in the other two families are not stable, and seem to differ from the fundamental family only in their larger mass. While the 2008 Nobel Prize for Physics was awarded for explaining why these other matter particles might existw1, physicists are still trying to work out why there are exactly eight of them.

Matter particles can ‘communicate’ with each other in up to four different ways, by exchanging different types of messenger particles named bosons (one type for each of the four interactions), which can be imagined as little packets of energy with specific properties. The strength and the range of these four interactions (the fundamental forces) are responsible for the hierarchy of matter.

Three quarks are bound together by the short-range strong interaction to form hadrons (particles formed of quarks) – the protons (two up- and one down-quark) and neutrons (one up- and two down-quarks) of the atomic nucleus. Up-quarks have an electric charge of +2/3 , down-quarks of –1/3 , which explains the positive charge of protons and the uncharged state of neutrons.

How are the electrons then attracted to the nucleus to form an atom? Since protons have a positive electric charge and electrons a negative electric charge, they attract each other via the long-range electromagnetic interaction, forcing the light electrons into an orbital around the heavy nucleus. Several atoms can form molecules, which are the material basis of life.

Since all these particles have a mass, they also attract each other through gravitation – but this long-range force, the third type of interaction, is so very weak (about 38 orders of magnitude weaker than electromagnetism) that it only plays a role when many particles pull together. The combined gravitational attraction of all protons and neutrons of Earth is what keeps you from floating off into space.

Finally, there is the weak force (actually stronger than gravity, but the weakest of the other three) – with a very short range – which allows the transformation of one type of quark into another, or of one type of lepton into another. Without these transformations, there would be no beta-decay radioactivity, in which a neutron is converted into a proton, i.e. a down-quark is transformed into an up-quark (for a discussion of beta-decay radioactivity, see Rebusco et al, 2007). Furthermore, the Sun would not shine: stars draw the energy they radiate from the process of fusion (for a further explanation, see Westra, 2006), in which a proton is turned into a neutron by the transformation of an up-quark into a down-quark – in other words, the reverse of beta decay.

Although the standard model has served physicists well as a means of understanding the fundamental laws of Nature, it does not tell the whole story. A number of questions remain unanswered, and experiments at the LHC will address some of these problems.

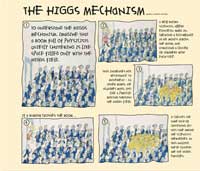

A ‘massive’ problem – the Higgs field

experiment, which may find the

elusive Higgs boson

Image courtesy of CERN

One of the open questions is: why do particles (and therefore matter) have mass? If particles had no mass, no structures could exist in the Universe, because everything would consist of individual massless particles moving at the speed of light. However, the mass of particles causes mathematical problems.

In the 1960s, an idea was developed to explain the weak force and the electromagnetic force within the same powerful theory, which described electricity, magnetism, light and some types of radioactivity as all being manifestations of a single underlying force called, unsurprisingly, the electroweak force. But in order for this unification to work mathematically, it required the force-carrying particles to have a mass. However, it was unclear how to give these particles a mass mathematically. So in 1964, physicists Peter Higgs, Robert Brout and François Englert came up with a possible solution to this conundrum. They suggested that particles acquired mass by interaction with an invisible force field called the Higgs field. Its associated messenger particle is known as the Higgs boson. The field prevails throughout the cosmos: any particles that interact with it (this interaction can be imagined as a kind of friction) are given a mass. The more they interact, the heavier they become, whereas particles that never interact with the Higgs field are left with no mass at all (see cartoon).

This idea provided a satisfactory way to combine established theories with observed phenomena. The problem is that no one has ever detected the elusive boson. The difficulty in finding it (if indeed it exists) is that the theory does not predict its mass, so it has to be searched for by trial and error.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

Using high-energy particle collisions, physicists create new particles – and search among them for the Higgs boson. The search has been on for the past 30 years, using higher and higher energies, but the particle is still to be found – presumably the energies used so far have not been high enough. As it stands, the Higgs particle must have a mass at least 130 times that of the proton. Scientists believe that the energy generated by the LHC – seven times higher than that used in any other collisions so far – should suffice to detect the Higgs boson.

Two of the experiments at the LHC, called ATLAS and CMS, will search for traces from the decay of the Higgs particle, which is believed to be very unstable. Proving its existence would be a great step in particle physics, since it would complete our understanding of matter. If, however, the Higgs boson is not found, this will mean that it is either even heavier than the LHC can detect, or simply that it does not exist after all. In that case, one of the competing theories that have been proposed may turn out to be true instead. Otherwise, theoretical physicists would be sent back to the drawing board to think of a completely new theory to explain the origin of mass.

The dark side of the Universe

There is another important aspect of particle physics that the standard model cannot explain: recent observations have revealed that everything we ‘see’ in the Universe (stars, planets, dust) accounts for only a tiny 4% of its total mass and energy (in the form of radiation and vacuum fields, such as the Higgs field). Most of the Universe, however, is made up of invisible substances that do not emit electromagnetic radiation – that is, we cannot detect them directly with telescopes or similar instruments. These substances only interact with ‘normal’ matter through gravity, not through the other three fundamental forces. We can, therefore, only detect them through their gravitational effects, which makes them very difficult to study. These mysterious substances are known as dark energy and dark matter (as discussed in Warmbein, 2007, and Boffin, 2008).

ghostly ‘ring’ of dark matter in

the galaxy cluster Cl 0024+17

(ZwCl 0024+1652). Photograph

taken using the Hubble Space

Telescope

Image courtesy of NASA, ESA, M.J.

Jee and H. Ford (Johns Hopkins

University); image source:

Wikimedia Commons

Recent observations suggest that dark matter makes up about 26% of the Universe. The first hint of its existence came in 1933, when astronomical observations and calculations of gravitational effects revealed that there must be more ‘stuff’ present in and around galaxies than telescopes could detect. Researchers now believe not only that the gravitational effect of dark matter allows galaxies to spin faster than would be expected from their observable mass, but also that the gravitational field of dark matter deviates the light from objects behind it (gravitational lensing; for a brief description of gravitational lensing, see Jørgensen, 2006). These effects can be measured, and they can be used to estimate the density of dark matter even though we cannot directly observe it.

But what is dark matter? One idea is that it could consist of supersymmetric particles – a hypothesised full set of particle partners for each of the twelve particles described in the standard model (see diagram).

The concept of supersymmetry postulates that for each known matter and messenger particle (e.g. the electron and the photon – the messenger particle of the electromagnetic force), there is a supersymmetric partner (in this case, the s-electron and the photino). In a supersymmetric world, these would have identical masses and charges to their partners in the standard model, but their internal angular momentum (called spin, measured in units of Planck’s constant) would differ by 1/2 unit. Matter particles normally have a spin of 1/2, while messenger particles have a spin of 1. Changing the spin by 1/2 unit would transform matter particles into messenger particles, and vice versa.

of the standard model, a

supersymmetric partner is

postulated.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

But what does supersymmetry have to do with dark matter? If the theory of supersymmetry is correct, then the Big Bang should have produced many supersymmetric particles. Most of them would have been unstable and decayed, but the lightest supersymmetric particles could have been stable. And it is these lightest supersymmetric particles which may linger in the Universe and cluster into big spheres of dark matter, which are thought to act as scaffolding for the formation of galaxies and stars inside them.

However, none of those supersymmetric particles have yet been detected – again, perhaps because their masses are so large that they are outside the range of particle accelerators less powerful than the LHC, as with the Higgs boson. So if they existed, even the lightest ones would have to be very heavy: rather than having the same mass as their supersymmetric partners (as originally proposed), they would have to have much higher masses. Supersymmetry is also used as a possible explanation for other, more complex puzzles in particle physics. So if any of the LHC experiments can detect and measure the properties of these particles, it would mean a significant advance in our understanding of the Universe.

The lost anti-world?

Now we have heard about matter, dark matter and dark energy – but in the early Universe, there was even more: we have good reasons to believe that a tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the Universe was filled with equal amounts of matter and antimatter. When particles are produced from energy, as in the Big Bang or in high-energy collisions, they are always created together with their antimatter counterparts. As soon as the antimatter particle meets a matter particle, both are annihilated, and the annihilation process transforms their mass back into energy. So, in the Big Bang, both matter and antimatter should have been produced in equal amounts, and then have wiped each other out entirely. Yet, while all the antimatter from the Big Bang disappeared, a small amount of matter was left over at the end of the process: this is what we consist of today. How could this have happened?

Antimatter is like a mirror image of matter. For each particle of matter, an antiparticle exists with the same mass, but with inverted properties: for example, the negatively charged electron has a positively charged antiparticle called the positron. Antimatter was postulated in 1928 by physicist Paul Dirac. He developed a theory that combined quantum mechanics and Einstein’s theory of special relativity to describe interactions of electrons moving at velocities close to the speed of light. The basic equation he derived turned out to have two solutions, one for the electron and one that described a particle with the same mass but with positive charge (what we now know to be the positron). In 1932, the evidence was found to prove these ideas correct, when the positron was discovered to occur naturally in cosmic rays. These rays collide at high energy with particles in the Earth’s atmosphere: in these collisions, positrons and antiprotons are generated even today.

For the past 50 years and more, laboratories like CERN have routinely produced antiparticles in collisions and studied them, demonstrating to very high precision that their static properties (mass, charge and magnetic moment) are indeed similar to those of their matter particle counterparts. In 1995, CERN became the first laboratory to artificially create entire anti-atoms from anti-protons and positrons.

If the amounts of matter and antimatter were originally equal, why did they not annihilate each other entirely, leaving nothing but radiation? The fact that matter survived while antimatter vanished suggests that an imbalance occurred early on, leaving a tiny fraction more matter than antimatter. It is this residue from which stars and galaxies – and we – are made. Physicists today wonder how this imbalance could have arisen.

One of the LHC experiments (LHCb) seeks a better understanding of the disappearance of antimatter by studying the decay rates of b quarks – which belong to the third quark family (see the diagram of the standard model) – and comparing them with those of anti-b quarks. It is already known that their decay rates are different, but more detailed measurements are expected to give valuable insights into the precise mechanisms behind this imbalance.

The primary soup

the Universe from the Big Bang

to the present day.

Click to enlarge image

Image courtesy of CERN

To answer all the above questions, physicists will collide protons in the LHC. However, for part of the year, beams of lead ions will be accelerated and collided instead, and the products of these collisions will be analysed by ALICE, the fourth large experiment in the LHC (besides ATLAS, CMS and LHCb).

About 10-5 seconds after the Big Bang, at a ‘later’ phase of the Universe, when it had cooled down to a ‘mere’ 2000 billion degrees, the quarks became joined together into protons and neutrons that later formed atomic nuclei (see the image of the history of the Universe). And there the quarks remain, stuck together by gluons, the messenger particles of the strong force (see the diagram of the standard model). Due to the fact that the strength of the strong force between quarks and gluons increases with distance, in contrast to that of other forces, experiments have not been able to prise individual quarks or gluons out of protons, neutrons or other composite particles, such as mesons. Physicists say that the quarks and gluons are confined within these composite particles.

Suppose, however, that it were possible to reverse this process of confinement. The standard model predicts that at very high temperatures combined with very high densities, quarks and gluons would exist freely in a new state of matter known as quark-gluon plasma, a hot, dense ‘soup’ of quarks and gluons. Such a transition should occur when the temperature exceeds around 2000 billion degrees – about 100 000 times hotter than the core of the Sun. For a few millionths of a second, about 10-6 s after the Big Bang, the temperature and density of the Universe were indeed high enough for the entire Universe to have been in a state of quark-gluon plasma. The ALICE experiment will recreate these conditions within the volume of an atomic nucleus, and analyse the resulting traces in detail to test the existence of the plasma and study its characteristics.

In the second article (Landua, 2008), Rolf Landua introduces the LHC technology and the four large experiments, ATLAS, CMS, LHCb and ALICE.

References

- Boffin H (2008) “Intelligence is of secondary importance in research.” Science in School 10: 14-19.

- Jørgensen, UG (2006) Are there Earth-like planets around other stars? Science in School 2: 11-16.

- Landua, R (2008) The LHC: a look inside. Science in School 10: 34-45.

- Rebusco P, Boffin H, Pierce-Price D (2007) Fusion in the Universe: where your jewellery comes from. Science in School 5: 52-56.

- Warmbein B (2007) Making dark matter a little brighter. Science in School 5: 78-80.

- Westra MT (2006) Fusion in the Universe: the power of the Sun. Science in School 3: 60-62.

Web References

- w1 – The 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded jointly to Yoichiro Nambu ‘for the discovery of the mechanism of spontaneous broken symmetry in sub-atomic physics’ and to Makoto Kobayashi and Toshihide Maskawa ‘for the discovery of the origin of the broken symmetry which predicts the existence of at least three families of quarks in nature’. For more details of their work, see: http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2008/press.html

Resources

- A much more detailed account of the standard model and the LHC experiments can be found in Rolf Landua’s German-language book:

- Landua R (2008) Am Rand der Dimensionen. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp Verlag

- The NASA website has a good description of the Big Bang theory: http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/bb_theory.html

- The Particle Adventure website provides teaching activities, including a good explanation of the standard model: http://particleadventure.org

- To find out more about the Higgs boson, see:

- The Heart of the Matter: Inside CERN: www.exploratorium.edu/origins/cern/ideas/higgs.html

- National Geographic’s interactive pages on the Higgs boson: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/03/god-particle/particle-interactive.html

- The National Geographic corresponding article: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2008/03/god-particle/achenbach-text

- To learn more about antimatter, see:

- The Live from CERN website, which explains what antimatter is, where it is made, and how it is already part of our lives: http://livefromcern.web.cern.ch/livefromcern/antimatter

- The CERN website, with information on Angels and Demons and scientific background material on antimatter: http://public.web.cern.ch/Public/en/Spotlight/SpotlightAandD-en.html

- The official website of the Angels and Demons film: http://www.angelsanddemons.com

- A portal to the top ten antimatter websites: www.anti-matter.org

- An online video by BBC/OU/VEGA explaining antimatter: www.vega.org.uk/video/programme/14

- For an introduction to supersymmetry, see: http://hitoshi.berkeley.edu/public_html/susy/susy.html

- To find out more about dark matter and dark energy, see:

- A media package for teaching dark matter provided by the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics: http://www.perimeterinstitute.ca/Perimeter_Explorations/The_Mystery_of_Dark_Matter/The_Mystery_of_Dark_Matter

- A video about evidence for dark matter, revealed by the Hubble Space Telescope, on the Space.com website: www.space.com/common/media/video.php?videoRef=150407Dark_matter

- A video describing physicist Patricia Burchat’s search for dark matter and dark energy: www.ted.com/index.php/talks/patricia_burchat_leads_a_search_for_dark_energy.html

- An article explaining dark energy on the Physics World website: http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/print/194

- For information on the quark-gluon plasma, including a comic (available in English, French, Italian and Spanish) on the soup of quarks and gluons, see the children’s corner of the ALICE experiment website: http://aliceinfo.cern.ch/Public/Welcome.html